Colonilization | Decolonization

Colonization

I have always had trouble grasping what it means to be an Indigenous person in Canada. Cultural identity can be a complicated thing to navigate especially when your parents come from two very different cultural backgrounds. I am Scottish on my mother’s side and Indigenous Canadian (Anishinabeg or Algonquin) on my father’s side. I have a fairly clear idea what it means to be Scottish and I feel that that this cultural identity is holding strong both in its traditions and in contemporary contexts. Indigenous identity on the other hand has its own set of challenges. Even though I grew up surrounded by Indigenous art and stories, I still felt somewhat unqualified to be an active spokesperson for my own culture. I am struggling along with other Indigenous youth to find my voice. I can trace this insecurity back to two things: not feeling I have contributed enough to the preservation of Indigenous culture and not explicitly looking Indigenous. While reflecting on this I thought why is that? Where does this insecurity come from? Indigenous Peoples today are at an apex of where two worlds collide. Generations of suppressed cultural identity and tradition alongside a manufactured “Indian” in mainstream media have resulted in my own identity crisis.

First, let me briefly explain colonization in Canada and its effects on its Indigenous Peoples which is partially responsible for my cultural insecurity. In the early 1600s, when Europeans came to what is now known as Canada, the colonists needed Indigenous people to survive in their new conditions and in wars between other European countries (Dickason, 1992). After the War of 1812 when Europeans and Americans settled their differences, Indigenous Peoples and their cultures were seen as impediments to progress. As the Europeans settled in North America, they created rules and regulations that “had two basic goals. One, to relieve us of our land, and two, to legalize us out of existence” (King, 2003). The most prominent piece of legislation in Canada is the Indian Act of 1876 that defined who and who is not “Indian” and effectively made “Indians” wards of the state to control them with the primary purpose of assimilating “Indians”.

When it was first released in 1876, the Department of Indian Affairs stated:

The Act is still in force today with amendments from its original legislation. The Canadian government gives the appearance of moving away from assimilation policies but even under new amendments, it reduces who is a status Indian; this means there will be no status Indians in seventy years (Whiteduck, 2009). The Canadian government used the Act to eradicate Indigenous cultural and language. Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools. Approximately 150,000 Indigenous children were forcefully removed from their families to enter these schools which were church-run and government funded (CBC, 2015). They ran under the policy of “aggressive assimilation” which resulted in “cultural genocide” starting in the 19th century and continuing until the late 20th century (All Points West, 2015). Up to 6,000 children may have died in these schools, and many suffered from emotional, physical and sexual abuse (John Milloy 1999, A National Crime. University of Manitoba Press). The goal was to “kill the Indian out of the child,” and even those who managed to survive these schools, it left a permanent hole in our cultural history. But Indigenous culture, knowledge and its expression still prevails today, surviving the Indian Act policies and laws.

There is a great level of fear and shame by Canadians surrounding the treatment of Indigenous Peoples by the Canadian Government. As a result, my father didn’t learn his traditional language because my grandparents feared that this would affect him negatively when looking jobs, “He would have an accent”. Abandonment was a survival strategy. And with an absence of literary tradition, the knowledge that is passed down orally through generations is much more easily lost. However, my father’s grandmother, mother and father passed on their knowledge orally through stories and practice.

On one hand, you have the government telling you that you must assimilate, and abandon your culture, while on the other hand during the 20th century there was great interest in mainstream media in portraying stories of “Indians” as a model for the environmental movement and as a lifestyle for the hippy movement. The depiction of Indigenous Peoples in the media greatly affects what we perceive Indigenous Peoples to look like, act like and speak like. “Indian and Indians cannot exist in the same imagination,” meaning what it truly means to be Indigenous cannot exist while the manufactured Hollywood version resides in our minds (King, 2003).

What we were left with from all this is a fractured cultural identity as a result of forced assimilation and shame. At the same time popular media feed us and the world false images of Indigenous People. Indigenous People like myself have to navigate constructed versions of Indigenous identity from popular media as well as negotiating a history of assimilation and oppression. My own identity is something that I had to discover and rediscover for myself. I am growing up in an era where Indigenous youth are redefining what it is to be Indigenous, a road that has to be carefully navigated and negotiated.

Decolonization

In order to find this authentic identity, I had to de-cloud my vision of inaccurate depictions of Indigenous Peoples through a process of decolonization. During this process you must “evaluate how you personally been affected by colonization, rid yourself of the emotional baggage and return to your ancestral tradition” (Simpson, 2011). This process was not just about decolonizing or how I see my identity and Indigenous Peoples, but is also about decolonizing how I approach my research itself. “Knowledge production from the West constitutes a form of imperialism that disregards and erases other types of knowledge” (Kermoal & Altamirano-Jimenez, 2016). I needed to find a new research paradigm that was in of itself decolonized in order to even begin researching. We need people to use traditional knowledge and philosophy as approaches, so that we are not looking at our own culture through a Western gaze. A large portion of my research process involved asking questions to older family members, sharing stories, and being active in my Indigenous community to see how perspective and knowledge changes on and off reserve, through different surroundings and life experiences, which is a fundamental part of decolonization.

Traditional knowledge and Indigenous philosophy is not treated as equal or valid as Western thought which creates an uphill battle for us when we talk about our experiences in an academic space. Oral history is seen as somehow unquantifiable and largely misunderstood. Storytelling as a process of knowledge sharing is at its core decolonizing. “Through speaking and writing, languages not only allow us to trace our history well beyond our own physical obliteration, they also contain our history” (Hagege, 2009). Shawn Wilson, an Indigenous researcher stated that a main approach to decolonizing research is putting the research into a context that Indigenous Peoples understand (Wilson, 2008). More and more Indigenous scholars are taking this approach to their work and are adding our beliefs, values and customs into their own research process. The importance of storytellers is understood by Indigenous Peoples and their ability to impart their own knowledge and life experiences into the telling of these stories.

“You don’t have anything if you don’t have stories,” (King, 2003). We are the stars of our own stories. We are real, authentic, complex and alive. When our stories as Indigenous Peoples are silenced and we are reduced to characters in the white narrative, we lose our voice, our perspective and our autonomy. Not only do I need to gather information through the process of others sharing their stories with me but I too must take the role of storyteller instead of simply that of a researcher or a designer. This is necessary in order for my work to have authenticity.

Indigenous stories are shared orally with nuances that space and time gives us. But that is not valued the same as written stories. They are seen as children’s stories, myths and fables which is a huge mistake. What is valued in Western society is permanence and concreteness. But what has been written about Indigenous people is usually by non-Indigenous writers and set in the past. “To try to write over that manufactured past is futile” (King, 2003), and that is why Indigenous writers today write in the present to share our image as one that is contemporary and alive. It is crucial that we avoid becoming “cultural ritualist,” feeding into false images of Indigenous people by dressing up and acting like an “Indian” to be recognized as such. is can also be seen in the work of Edward Sheri Curtis who photographed Indigenous Peoples across North America in the early 1900s, but would not photograph them as they were but would dress them up to look more “Indian”. As a designer, I have to find my own entry point to actively engage with my culture as others have done in the past as an act of resistance through clothing, personal objects, art, and other forms of expression, while also designing in the present as a response to contemporary realities.

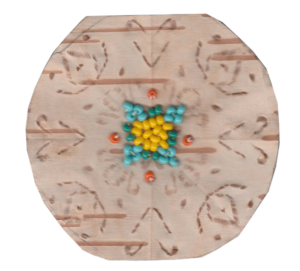

The way I have found a connection to traditional knowledge both as a person and as a designer is through beadwork and clothing. I come from a long line of incredible beaders on my grandmother’s side who have been making beautiful pieces of work for generations. I’ve always been interested in sewing and costume making which I had learned from my mother but until now I hadn’t engaged in traditional beading. Beads and beadwork have very strong connections to traditional knowledge, identity expression and acts of resistance.

The material used in these garments can suggest a location as to where the dress was made such as types of hide or beads. But Indigenous Peoples have been trading material between tribes, even before contact by Europeans. Therefore, it is also a reflection of their interactions and connections to other groups. There has always been an experimental attitude towards traditional dress and different materials from Italian glass beads, Chinese coins to British cotton cloth; variety added to the creativity and individualism of these garments. (National Museum of the American Indian, 2007). Beadwork is crucial in this expression of individuality and creativity. It “reflects what the people saw and what they had going on in their lives at the time” or record the history of a tribe or to ratify a treaty between tribes through woven belts (National Museum of the American Indian, 2007) (Crabtree & Stallebrass, 2009). When Indigenous Peoples were confined to reserves, the beadwork became more elaborate which is a reflection of the amount of time that they had and the desire to show the beauty and craftsmanship that cannot be stifled in their culture.

“For contemporary women artists, dresses are more than garments. They are evidence of a proud and unbroken tradition, links to the generations of women who came before them and bridges to the future” (National Museum of the American Indian, 2007). These garments have great power to share traditional knowledge from the making of them to being worn and subsequently passed on. It is a “literal embodiment of ancestral knowledge” (National Museum of the American Indian, 2007). Beadwork is a powerful tool for storytelling and creates an outward expression of identity and tradition that engages the viewer to learn more about it.

Visibility is really important and Indigenous stories have a growing audience, and not just stories about us but with us. “Shame can only take hold when we are disconnected from the stories of resistance within our own families and communities” (Simpson, 2011). Pride in oneself and one’s culture can counteract the destructive forces of colonization. New generations are following contemporary Indigenous artists and are now being influenced by such artists as Christi Belcourt. Christi has collaborated with the Italian fashion house Valentino for the 2016 Resort collection which featured her beaded designs on their gowns. Design can be used as a tool for empowerment and provide a dynamic forum for storytelling. Indigenous designers could delve into their traditional history and apply this knowledge to their practice. Engaging with traditional culture contributes to decolonization and resurgence.

Conclusion: Hybrid Life

It is impossible to lead a life like that of Indigenous Peoples before contact. Like many Indigenous Peoples, I live in a large city not surrounded by other Indigenous Peoples or culture. I live in a colonized world and I have to redefine what it means to be Indigenous, a road that has to be carefully navigated. I find this is more challenging in academic spaces. Growing up, I went to a Catholic school, where I was taught about Canada’s history and Indigenous Peoples by non-Indigenous teachers. I am an Indigenous person doing an MA at a British institution, studying the effects of colonialism as it relates to the resurgence and preservation of Indigenous knowledge. At times, the contrast in world views is quite stark. To survive, I must be secure in my own cultural identity to enable myself to apply Indigenous knowledge to my research, my process and my design work.

It is impossible to lead a life like that of Indigenous Peoples before contact. Like many Indigenous Peoples, I live in a large city not surrounded by other Indigenous Peoples or culture. I live in a colonized world and I have to redefine what it means to be Indigenous, a road that has to be carefully navigated. I find this is more challenging in academic spaces. Growing up, I went to a Catholic school, where I was taught about Canada’s history and Indigenous Peoples by non-Indigenous teachers. I am an Indigenous person doing an MA at a British institution, studying the effects of colonialism as it relates to the resurgence and preservation of Indigenous knowledge. At times, the contrast in world views is quite stark. To survive, I must be secure in my own cultural identity to enable myself to apply Indigenous knowledge to my research, my process and my design work.

We are in a time of reconciliation where the relationship between Canadians and Indigenous Peoples is evolving and I believe both can coexist and have something to learn from one another. It is this cultural plurality that creates intense richness in Canadian culture and this complexity can be celebrated and expressed through design. The education system has been a major source of oppression for Indigenous Peoples. But while education can hurt people, it can also heal. Indigenous Peoples can make their own space in academic settings while not compromising their own values and traditions in relation to knowledge sharing. It is possible to decolonize the academic space, to Indigenize it for oneself and create a place of resurgence for others down the line.

There is an Iroquois philosophy called the Seventh Generation Principle, which states that the decisions we make today need to be sustainable for our people seven generations into the future (Joseph, 2012). Seven generations from now I envision that Indigenous identity isn’t questioned the way it is today; through governmental policy, by non-Indigenous people, or compared with mainstream stereotypes. I will share this decolonization process, as it relates to research and design, to inspire and educate young Indigenous Peoples who face similar situations to help discover their identity and find their voice. This will enable them to transform from designers and Indigenous persons to Indigenous designers. This demonstrates the collaboration of these two worlds and creating a space for resurgence. We can use design to redesign the future by bringing along the authentic past, leaving the colonized view behind. We can create work that can still embody Indigenous values and principles, while not looking “explicitly traditional”, through the application of an Indigenous approach to design. Together we can create a new authenticity for Indigenous Peoples.

References

All Points West (2015) ‘Aboriginal languages in Canada can and should be made official, expert says,’ CBC News. Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/aboriginal-languages-in-canada-can-and-should-be-made-offcial-expert-says-1.3147759 (Accessed: 22 May 2017).

Altamirano-Jimenez, I. and Kermoal N. (2016) Living on the Land: Indigenous Women’s Understanding of Place. Edmonton: AU Press.

CBC News (2008) ‘A History of Residential Schools.’ Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/a-history-of-residential-schools-in-canada-1.702280 (Accessed: 22 May 2017).

Crabtree, C. and Stallebrass, P. (2009) Beadwork: A World Guide. New York City: Rizzoli International Publications.

Fleurie, T. (2016) ‘Indian Act isn’t easy to understand, according to chief,’ The Leader. Available at: http://www.tanakiwin.com/wp-system/uploads/2013/09/The-Eganville-Leader_March-16.16.pdf (Accessed: 22 May 2017).

Hagege, C. (2009) On the Death and Life of Languages. Translated from French by J. Gladding. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Indian Status (2015) Available at: http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/the-indian-act/indian-status.html (Accessed: 22 May 2017).

Joseph, B. (2012) ‘What is the Seventh Generation Principle,’ Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples. Available at: https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/seventh-generation-principle (Accessed: 22 May 2017).

King, T. (2003) The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Canada: House of Anansi Press.

National Museum of the American Indian (2007) Identity by Design: Tradition, Change, and Celebration in Native Women’s Dresses. New York: Smithsonian Penn Museum.

Olive Patricia Dickason (1992). Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Simpson, L. (2011) Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring.

Wilson, S. (2009) Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing Co.