What I did

From start to finish of this project, I have not only changed as a designer but also as a person. I entered this MA with the hopes of doing a project in relation to my culture and to figure out my own position as a designer. After graduating from my BA, I was unsure about what I wanted to do in design but I knew I wanted to position myself with an original voice and perspective in design. I wanted to follow my love of learning traditional techniques and figure out how I could combine my culture and my craft in a way that was not only meaningful for me, but added to a larger discourse.

From start to finish of this project, I have not only changed as a designer but also as a person. I entered this MA with the hopes of doing a project in relation to my culture and to figure out my own position as a designer. After graduating from my BA, I was unsure about what I wanted to do in design but I knew I wanted to position myself with an original voice and perspective in design. I wanted to follow my love of learning traditional techniques and figure out how I could combine my culture and my craft in a way that was not only meaningful for me, but added to a larger discourse.

To be honest, at times I found this very hard. Going through your history can be really emotionally taxing. My family has survived so much and taking the time to really reflect on it, I feel the ripples of destructive colonization and cultural genocide; we continue to pay the price for the generations that lost their culture. I felt guilty about not doing more to preserve my culture, and felt that my ability to claim Indigeneity was weakened. This project comes out of a desire to do more; more to honour my family that survived all this and to honour the knowledge that was saved in spite of all the efforts to get rid of it. To honour both my parents who shared their knowledge and skills with me and gave me the opportunity to explore these things in my life and in my work.

This journey started with a project that I began in the first year of my MA which was about redefining the definition of ‘Indian’ as it is written in Canadian legislation known as the Indian Act. In order to do this, I reached out to my family, friends and the broader Indigenous community to add their voices to the project by printing over all 73 pages of the Indian Act with their statements of what it means to be Indigenous. It helped me to begin to understand more about my own identity and solidified my desire to include my community as a part of my final project. I continued this process throughout my project in line with Indigenous values and with the emphasis on storytelling as a means of knowledge sharing and preservation.

The integration of the values was crucial to my research methodology which I determined early on needed to be a decolonized and Indigenous approach in order to have the authenticity and original perspective that I desired out of my project. Most of my research was either written by Indigenous writers or scholars, collected through conversations with Indigenous artists, including extensive discussions with my father to emphasize the importance of intergenerational knowledge sharing as traditional knowledge preservation and decolonization, as well as working with young Indigenous Peoples on and off reserve teaching art and integrating it with their culture. I needed to first listen to others, getting their perspectives, learn traditional techniques, combining that with my own experience before taking the role of the storyteller and being responsible for the knowledge that I now feel confident to share with others.

The integration of the values was crucial to my research methodology which I determined early on needed to be a decolonized and Indigenous approach in order to have the authenticity and original perspective that I desired out of my project. Most of my research was either written by Indigenous writers or scholars, collected through conversations with Indigenous artists, including extensive discussions with my father to emphasize the importance of intergenerational knowledge sharing as traditional knowledge preservation and decolonization, as well as working with young Indigenous Peoples on and off reserve teaching art and integrating it with their culture. I needed to first listen to others, getting their perspectives, learn traditional techniques, combining that with my own experience before taking the role of the storyteller and being responsible for the knowledge that I now feel confident to share with others.

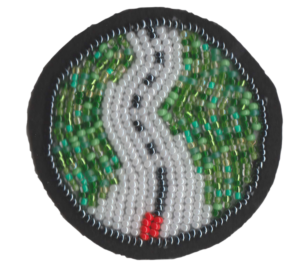

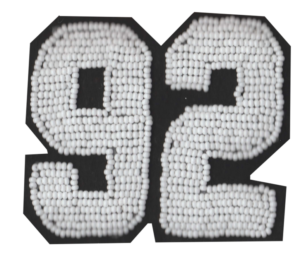

I learned how to do beadwork over the summer, a technique that I found bridged a lot of different worlds for me. I learned how to sew from my mother, who is a costume maker, and I learned traditional Indigenous stories from my father. Beads were brought over by the Europeans to North America and gave the Indigenous Peoples more variety and a greater ability to express themselves in their own work. It felt like the perfect medium for me to use for this project, bringing costume and Indigenous culture together, as well as the collaborative relationship between non-Indigenous and Indigenous people together. It is a true demonstration of two sides coming together to make something that does not compromise the integrity of the other. I applied both my background in fashion and comparing it alongside Indigenous clothing, worked with textile as a means of storytelling and clothing as a means of identity expression, while also looking at both in different contexts; bringing existing clothing systems together to create a contemporary outlook on both design and identity. I did this by using noncommercial items of clothing that are in relation to stages of education to show a reflection of a journey of Indigenous identity development and expression. The main audience of my project was Indigenous Peoples, but I’ve tried to create something that engages people’s interest and entices people to want to know more about the garments and therefore more about Indigenous identity and knowledge, using clothing as a system that most people can understand.

What I learned

I discovered that I am more affected by colonization that I had previously thought. The MA program pushed me to reflect on design and what is Indigenous design which forced me to think deeply within myself about these questions. This work has created the momentum for me to think about and to continue to explore the meaning of Indigenous design. In an Indigenous context collaboration and communications with others in the community is crucial to the work and practice.

I discovered that I am more affected by colonization that I had previously thought. The MA program pushed me to reflect on design and what is Indigenous design which forced me to think deeply within myself about these questions. This work has created the momentum for me to think about and to continue to explore the meaning of Indigenous design. In an Indigenous context collaboration and communications with others in the community is crucial to the work and practice.

As an Indigenous person working in Western contexts and academic spaces, I have faced people not understanding the needs of Indigenous design and research – breaking down stereotypes and education has been a part of the design process. There is a social responsibility that you have as an Indigenous designer that must always be considered, as your work has a direct effect on the people that it portrays. I have learned a lot about decolonizing my research approach and subsequently my approach to design itself. My research process had to keep Indigenous knowledge and ways of living into consideration and by doing so this work has become both decolonizing and reconciling.

A key thing that I learned through this process is having the researcher become the storyteller, which is an important role in Indigenous culture as someone who can impart wisdom and preserve oral tradition. It is something that I’ve aimed to keep as part of my work, even through my writing, trying to have an oral quality that allows the reader/writer relationship to have a personal quality to it. A part of this was also to critique the dominant Western way of research, and to not look at Indigenous design and culture with a Western gaze. Design can be a part of reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and Canadians, and working with Indigenous people, I have a better understanding of identity and its challenges as it relates to the general public while applying a holistic, land-based and two eyed seeing approach to knowledge.

A key thing that I learned through this process is having the researcher become the storyteller, which is an important role in Indigenous culture as someone who can impart wisdom and preserve oral tradition. It is something that I’ve aimed to keep as part of my work, even through my writing, trying to have an oral quality that allows the reader/writer relationship to have a personal quality to it. A part of this was also to critique the dominant Western way of research, and to not look at Indigenous design and culture with a Western gaze. Design can be a part of reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and Canadians, and working with Indigenous people, I have a better understanding of identity and its challenges as it relates to the general public while applying a holistic, land-based and two eyed seeing approach to knowledge.

What I want to do next

I want to apply this approach to projects that are beyond my personal identity into broader Indigenous communities by working with other Indigenous designers and understanding their processes. I still want to create a font that includes all Indigenous alphabets as a tool that can be used by other Indigenous designers to create more inclusive signage, packaging and give Indigenous language a space in Canadians daily lives (all packaging in Canada currently has both French and English translations).

I want to apply this approach to projects that are beyond my personal identity into broader Indigenous communities by working with other Indigenous designers and understanding their processes. I still want to create a font that includes all Indigenous alphabets as a tool that can be used by other Indigenous designers to create more inclusive signage, packaging and give Indigenous language a space in Canadians daily lives (all packaging in Canada currently has both French and English translations).

I also want to continue to do more writing about Indigenous Approach to Design and develop an approach that can help other Indigenous designers create work that is decolonizing, inclusive and adds to a new authenticity to Indigenous Peoples.

This project had been used as a case study for an Indigenous Approach to Design. I have applied what I’ve learned doing this project to my recent freelance work with Prosper Canada creating illustrations using animals from our territory to act as navigational tools, and with City of Ottawa creating land-based designs for their wayfinding symbol in the new transit systems that are situated on Algonquin territory. These projects are also collaborative and participatory, furthering my engagement with my community. I want to continue to talk about Indigenous arts and culture in an academic space not only in terms of Indigenous knowledge but as it applies to design practice to allow more Indigenous people into these spaces while providing new perspective to non-Indigenous people and creating better understanding for everyone involved.

Trying to figure out who you are is hard enough, but when, for generations, people have tried really hard to eliminate your cultural past and tradition, it can be even harder. I’m glad to be a part of this history and a part of my culture’s resurgence. I hope that it can be vibrant into the future and that more young Indigenous people use design as an entry point into our culture and create a broader discourse of Indigeneity in design so that they too can be an authentic source of inspiration. And I hope future generations do not have to face this trauma.

Trying to figure out who you are is hard enough, but when, for generations, people have tried really hard to eliminate your cultural past and tradition, it can be even harder. I’m glad to be a part of this history and a part of my culture’s resurgence. I hope that it can be vibrant into the future and that more young Indigenous people use design as an entry point into our culture and create a broader discourse of Indigeneity in design so that they too can be an authentic source of inspiration. And I hope future generations do not have to face this trauma.

When you are doing a project about and Indigenous Peoples, there is a great responsibility that you have in portraying them accurately and with their support and participation. A lot of the time I’ve been told that I shouldn’t worry about what they think about my work or whether or not they approve it, but I just couldn’t do that. When there are so few Indigenous voices in design, you need to think about what you are adding to this discourse and its effects on the community. It’s a blessing and a curse. The pool is small, and with my work I don’t just make ripples, I make waves. At times, it was quite challenging but I found confidence in my own voice and knowledge that I knew whatever I did, I would make my people proud, and that has been really rewarding.

“If research doesn’t change you as a person then you haven’t done it right” – Shawn Wilson, Research Is Ceremony

Collaborative work

I’ve been a part of the Degree Show in many different ways from the very beginning. I started on the concept development team and was a key person in the articulation of the concept, doing the majority of the writing at the start of the idea generation process. I spent many hours during my term break on Skype with other members of the concept team, as well as in meetings with the design team in order to monitor the progress and keep up to date with any changes.

I’ve been a part of the Degree Show in many different ways from the very beginning. I started on the concept development team and was a key person in the articulation of the concept, doing the majority of the writing at the start of the idea generation process. I spent many hours during my term break on Skype with other members of the concept team, as well as in meetings with the design team in order to monitor the progress and keep up to date with any changes.

I’ve had a key role in the organization of the degree show as the show’s supervisor. This has involved keeping track of all the teams and all the information needed to be collected from our peers, attending all sub-team meetings and acting as a liaison between the teams and with the university staff. I am also on the publication team doing writing, conducting interviews with everyone in the year group, and collecting other content for the publication. I have sacrificed a lot of my own time for the degree show, but I truly enjoy collaborative work and getting people to come together, bringing in everyone’s individual strengths to produce something better than we could have done on our own.